This report comes from second year undergraduate History & Politics student Kit Boulting-Hodge, who is conducting a research project for the Cheltenham Labour Party as part of HM5002 Engaging Humanities. It is an example of how our students can gain valuable experience and develop a number of transferrable skills, while contributing to important heritage work in the area.

I’ve been working with Cheltenham Labour Party to gather information about the campaign opposing the 1984 state-imposed ban on trade unions at GCHQ. This project was triggered by the death of the prominent figure Mike Grindley. Before his death, Mike was concerned that the lessons from this campaign, fought by 14 GCHQ workers, would be lost and the current government may try again to ban trade unions at GCHQ. Interviewing trade union activists from the time of the protest, including one of the 14, has been an enlightening experience.

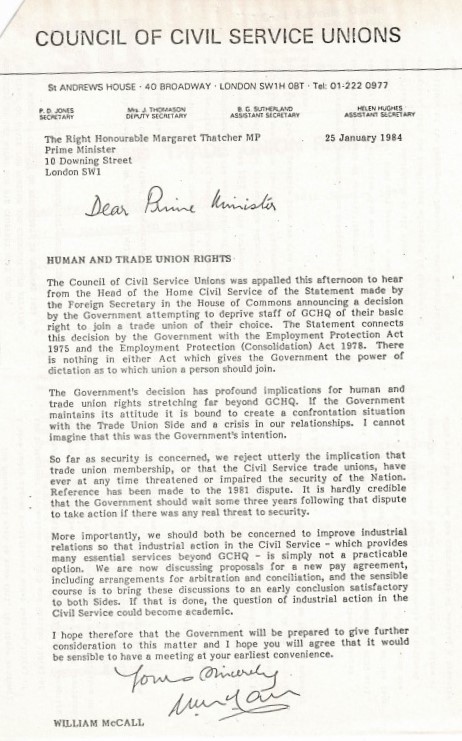

The move to de-unionise GCHQ was premeditated and was initially rejected at multiple stages by various parliamentary select committees, even some dominated by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative allies. There was a court battle, which the government lost. This, however, set the precedent that the government has the power to de-unionise workplaces if due process is followed. The case cost the government huge amounts of money, but that was just the beginning.

When the government finally formulated their plan, each employee was given two options:

1: accept the money on offer as compensation to leave the trade union and have the choice to be part of the Staff Association. The Association was obviously a sham replacement that didn’t have the organisational structure of a trade union. Staff morale was incredibly low at this point, but this was the only viable way to create the impression that the workers were being represented.

2: refuse to leave the trade union and breach the new contract, which meant that the employee could be fired.

The unions, however, offered a third option: not to sign. This worried the government because most of the workers seemingly supported this option, right up until management pressed the employees for a final decision. Initially, apart from 14 workers, all employees agreed to stay at GCHQ, but many soon quit and found jobs elsewhere.

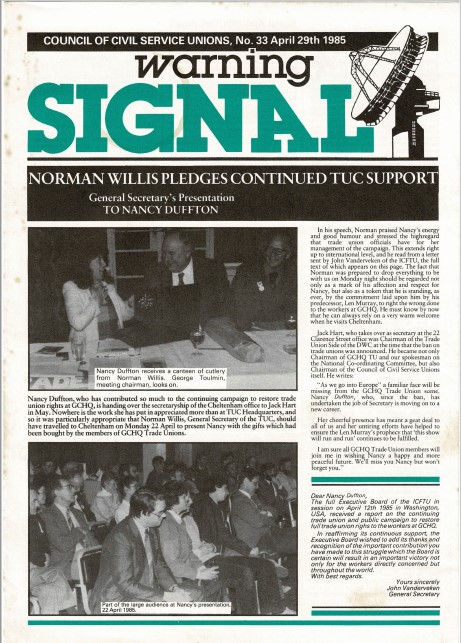

The following years, extending through John Major’s period of office, were focused on finding a peaceful means to reverse the government’s decision. The protestors went on annual marches, and they held regular meetings to check on progress. The unions never relented. Even in my interviews that were not directly related to GCHQ, some respondents mentioned GCHQ towards the end.

The most important outcome of the dispute is that Thatcher’s government failed. Eventually, in 1997, the ban on trade union membership at GCHQ was lifted, with the exception that the parts of GCHQ dealing with secret and sensitive information were not allowed to strike. In essence, Tony Blair had agreed with the Thatcher government that hundreds of days of work had been lost because of the dispute. This infuriated most of the 14 campaigners. By this stage, the dispute had been going on for over 13 years, so it had inevitably lost some momentum.

All but one of the original 14 campaigners received the Trades Union Congress award. One of the protestors refused the award because of the continuing ban on strike action by sections of GCHQ. It is often difficult for trade unions to win their battles. The achievement at GCHQ was one of a kind.