This is the second of four projects that undergraduate History students at the University of Gloucestershire are conducting for the Centre in 2023, in partnership with a number of local heritage institutions in the area, including City Voices. This project involves students Matthew Morgan, Holly Lasfar, Tyler Tomlin, and Olivia Jordan.

Our group project focuses on the history of places of refuge and support for women and girls in Cheltenham and Gloucester. Specifically, we have studied the Home of Hope, Park Street Mission, North Parade Home for Girls, and Cheltenham Female Orphan Asylum. We are interested in researching this subject to learn about the various ways Gloucestershire aided women in need in the past. When we started the project we assumed that many of the women who sought help from these places were victims of abuse or violence, but we have since learnt that some of these places of refuge, like the Home of Hope, were places that looked to support and train girls and young women who were experiencing problems in their lives.

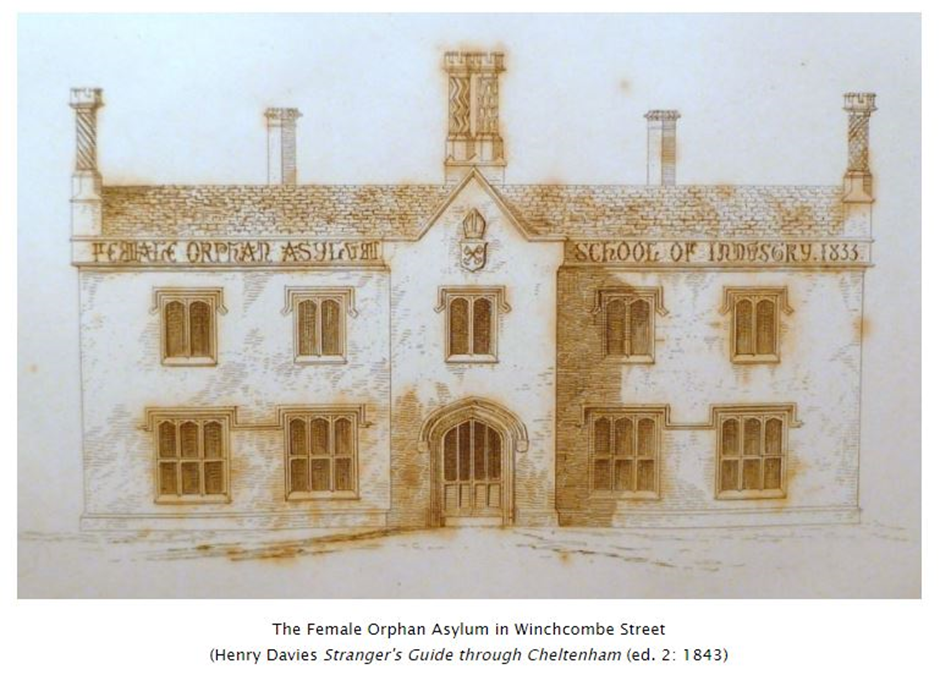

Our research into the evolution of the Cheltenham School of Industry, founded in 1806, has revealed some of the provision of refuge spaces for women and girls in Cheltenham in the early nineteenth century. The School of Industry’s founder was Queen Charlotte, wife of King George III. Conducting research through the examination of archival documents and numerous newspaper reports makes clear that the school remained a respected site of refuge. It was well-funded by local subscribers. Upholding religious teachings and importantly focusing on the training of girls as respectable domestic servants, the home played a significant role in ensuring that the girls were successfully engaged in employment on their departure. In honour of its founder, the school was renamed Charlotte House in the 1950s. The building was demolished in 1958.

We are also looking into a number of small refuges in Cheltenham and Gloucester, including those run on a weekly and part-time basis, such as the Park Street Mission in Gloucester. We are interested in the religious underpinnings of these women’s refuges, as well as the role of women in the official and unofficial hierarchy of these organisations. Park Street Mission is well-documented. It was a well-run refuge, which came as a surprise to us when considering the period in which these institutions existed. There appears to have been a consistent membership of the Mission, and from this we can determine the potential positive impact such refuges had on their membership. Much of the available information on the Mission derives from the organisation itself, and collecting this information means that the worthwhile story of women’s refuges can now be told.

Another interesting aspect of these refuges was their ‘sale of work’ events. These are particularly evident in our research into the Cheltenham Female Orphan Asylum. These refuges had been set up to aid women and girls who had lost their way and who now needed support. The training provided by these organisations, and the accompanying sale of work events, enabled women to develop skills that would help them find gainful employment. The sales also generated income for the refuges themselves.

Religion played a key role in the way these refuges operated, and it is interesting to see how closely linked key members of local churches were to these organisations. This is evident in the example of the Cheltenham Female Orphan Asylum subscriber lists and from the membership of the management boards. Highlighting these important elements in our research has helped us to decide how best to convey the stories of the refuges.